Jeff Rennicke is a writer, a photographer and a storyteller in Bayfield, Wisconsin. He is the Executive Director at Friends of the Apostle Islands National Lakeshore.

“Pay attention. Things get really interesting below the surface. Wherever you are, there’s more going on than a superficial glance will reveal to you.”

“I was a freelance writer for 20 some years and traveled to six different continents, wrote nine books and hundreds of magazine articles and was traveling all the time. Just the complete traveling lifestyle, which is wonderful. For National Geographic Traveler, Sierra, Backpacker, Canoe. 44 different magazines, at least. Anyone who would pay me along the way, the freelance lifestyle. And it’s wonderful. There’s a true privilege in bouncing across the world telling stories. And I enjoyed it. I loved it. But there’s also a cost.

Edward Abbey once said “To be everywhere at once is to be nowhere forever.” And I got to the point where I was beginning to feel that way, and I couldn’t really articulate it, but it all came together at one moment. I had just returned from someplace that, prior to the trip, I couldn’t have found on a map. I still wasn’t quite sure the right pronunciation of it. And I was completely jet lagged.

I walked down to the lake, just five blocks from our house, really early in the morning as everybody else was asleep. I’m looking out at this incredibly beautiful sunrise with a pair of ducks—a species I had never seen in this area before—and this incredible beauty. And I just thought to myself, “How many miles do I need to travel before I begin to see the beauty right in my own backyard?” It seemed ridiculous because all I was doing, in this beautiful place, was leaving.

Then the phone rang. It was my editor from National Geographic Traveler. A story I had written about another far off place had won something called the Lowell Thomas Travel Journalism Award. He was very excited about that. And in appreciation for that, he said, “We’d like you to go anywhere you want to go for your next story.” And I said something that I think surprised him. I know it surprised me.

I said, “Could I just stay home?” At first he thought that meant I didn’t want to write anymore. I said, “No, I live in this incredibly beautiful, storied landscape. And all I’m ever doing is leaving. I would like to see [if I] can bring the same poetic sensibility, the same observation skills, the same listening skills, the same depth of attention to my own backyard that I bring to places far away that win awards for the magazine.”

Luckily he didn’t fire me. He said, “That sounds like a great idea.” Kind of a travel writer stays home idea.

We rented a sailboat, the Reverie, and we had friends who captained that boat. We sea kayaked the islands, we toured the lighthouses. We did all the things that other people were getting to do in our backyard and we weren’t getting to do because we were always driving other places.

I wrote a story called Seven Shades of Blue and about Lake Superior and the Apostle Islands that appeared in National Geographic Traveler. And to this date, it’s one of my favorite stories I’ve ever done because it was so heartfelt. And I realized, yes, I could find beauty in my home area. So, that was the end of my travel writing career. I decided I don’t want to go broad, I’d rather go deep. And so I’ve decided to put my roots down into the north woods of Wisconsin and the Apostle Islands in particular and see if I can’t use the rest of my time on this precious planet to go deep.

__

[There’s a] quote from my friend and mentor Richard K. Nelson, who was born and raised in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and ended up spending a lifetime living among indigenous people up in Alaska. He said “There is more to learn from climbing a single mountain a hundred times than climbing a hundred different mountains.” At first, when I was a travel writer, I might’ve questioned that. It’s a great conversation to bring up with friends. Do they agree with that or not? I have come to agree with it because a beautiful place, a place that touches your soul, is endlessly deep with stories and information. The problem is we skip across the water like a stone rather than letting ourselves sink into one place. And so I’ve taken that as kind of a mantra.

The other one that’s always been very important to me is a quote by Marcel Proust who says “The true journey of discovery begins not in seeking new landscapes, but in having new eyes.” And my photography, the use of photography to develop sense of place, really revolves specifically around that quote. Trying to have new eyes to see the same place in new light all the time.

Some people travel their entire lives. Other people travel for a while and then begin to want to sink in deep. And we’ve all experienced this. You’re out on a trip to someplace exotic and everything seems cool. The street names are different. and the food smells and the languages that you hear on the street. And so your senses are peaked all the time. I think that’s one of the beauties of vacation, is to enjoy the exotic because it peaks us. It makes us feel more alive. Then you come home and you turn that off. You pay no attention to the beauty and uniqueness of your own backyard. And so I want to see if I can keep that turned on and live my life as if I’m looking constantly with new eyes in my own backyard.

For my master’s thesis at Bennington College, I did a comparison of two writers who are completely opposite in their viewpoint. John Muir was an incredible traveler for his time. An exclamation point in hiking boots. And John Burroughs literally would walk out into the backyard of his Woodchuck Lodge and literally sit on a stump and wrote some of the most popular nature books ever written. 25 books from writing on a stump.

I compared and contrasted and looked at the different values of each. There’s value in each. But there’s no value in turning it off completely. Either way, if you turn it off when you come home, you’re missing something. If you love your home and don’t pay attention to where you’re going on a trip, you’re missing something. It’s not either/or.

Richard Nelson said something else that’s important. People used to say to him, “Well, yeah, sure. You picked Alaska. That’s your spot. Of course.” And he wrote in his book The Island Within, “It’s not so important where you choose, it’s that you choose.” That it’s a cognitive movement. A conscious decision to lay down your life in one place. It could be Kentucky. It could be Alabama. It could be Wisconsin, but you have to make that choice to attempt to keep yourself tuned to all that.

__

What I love about this place is it’s duality. It is a national park. It is a designated wilderness. And for the person who doesn’t know the stories, who doesn’t want to go deep into a history, it can seem like a pristine untouched place. It’s not. Bill Cronin, another friend and mentor called this landscape a storied landscape, a storied wilderness. That might seem a contradiction, but the story of the Apostle Islands is story of people and nature meeting at the edges. There’s development out there. Quarries and old farms out there. There’s a lot of logging. There’s shipwrecks out there. There’s human footprints in the strangest places. There’s an old car rusting away on Sand Island. There are shipwrecks poking out of Julian Bay. On Oak Island, there’s an old safe from the timber company if you know where to look.

One of the beauties of it, is it’s an intersection between humans and nature, which is what interests me. There are places that have much less human impact than here. And there’s places that have too much human impact. This seems to be a place where that is a natural connection. Aldo Leopold said, “I’m interested in both nature and the human relationship to nature.” And he could have been talking about the Apostle Islands.

__

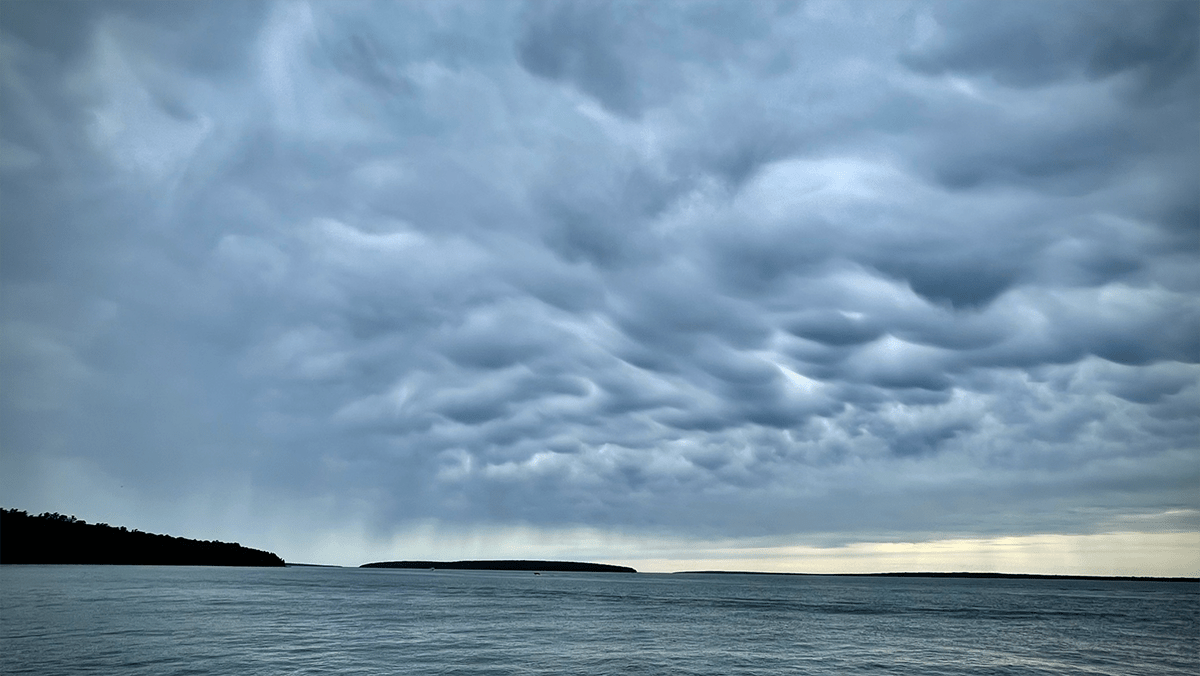

One of the reasons I love photography is that it is something you are not in control of. You have to show up and you have to have the right equipment and you have to have the knowledge to make it work. But what happens in nature, you can’t control. It’s not still life photography, where you’re in a studio and you can set the lights a way you want, move the subject this way or that way. You take what you get. And so there’s this wonderful combination between feeling in control…I have the right gear and my batteries are charged. I have the knowledge of the f-stop and the shutter speed and all that. You feel like there’s a sense of control, but what’s in front of the camera, you have zero control on. You can control your angle to it, but you can’t control when the sun’s going to come up or when the lightning’s going to hit.

And so again, it’s that interface between the human element, the photographic element and nature. As our friend, Julian Nelson, 101 year old commercial fishermen used to say, “The lake is the boss.”

The lake is the boss. And so you go out on the lake with respect and with knowledge and with the right equipment. And then you just wait and see what happens

I have seen thunderstorms a dozen times happening where you were staying, Little Sand Bay, which is the western side of the peninsula, that never made it over the peninsula to Bayfield, which is on the eastern side of the peninsula. I could see the lightning, but it was far off. It was over you not over me. And so I poked out of the harbor with the assurance that I could get back within a relatively safe amount of time and that the storm probably wasn’t going to come over the hump. But the light did. And the light lit up for about five or seven minutes over Basswood Island. And just showed us a glimpse of beauty.

Photography is the art of capturing those glimpses of beauty when they happen. And I was there.

It’s magic. But the one thing that people don’t understand is that for every moment of magic there’s hours of patient waiting. One of the greatest examples of photography exhibits I’ve ever seen was one on Ansel Adam’s hundredth birthday. I think it was in Chicago where we saw it, but you think of Ansel Adams as this incredible icon of photography, and you could put up a dozen of his prints and you would be slack-jawed in front of each one of them. But what this exhibit did was to show some of his mistakes or some of his moments when it didn’t happen. And it really gave you a sense that for every iconic photograph, whether it’s Ansel Adams or Art Wolfe, Beth Wald, or any of these other incredible photographers, for every 1/100th of a second exposure that they captured this magic, there are hours of times when it just doesn’t happen. People forget that. They think every moment you go out there is magic. It’s not. You pay your dues.

__

[Lake Superior is] incredibly fragile. It’s actually geologically a tiny puddle, even though as you say, it is the largest lake in the world by surface area. In terms of the impacts that we can have on it, they’re myriad, unfortunately. Everything from source pollution…air pollution is a bigger problem up here than you might think because the lake is so huge that the surface area for particulate matter to fall into is also huge. Water pollution comes from the tributaries coming in, but most of it comes directly off the land as runoff. They’re studying that now and it’s much more difficult to control. You can control the quality of a tributary stream bringing in pollution. But how do you control runoff from a thousand plus miles of perimeter?

You’re talking different states and in this case, you’re actually talking two different countries. So the complexities of trying to manage Lake Superior from a legislative standpoint are incredibly complicated. You can list the water pollution and the air pollution and the invasive species, and all of that is deeply important, but it all begins with an understanding of the resource. And as you hinted at just a moment ago, people don’t understand Lake Superior. If you’re not familiar with Lake Superior and you hear the term lake, you think of your backyard pond that you used to fish with your grandpa or your uncle, and you don’t understand it’s 360 miles long and 160 miles wide. It takes sunrise a half an hour to cross Lake Superior. That’s how big it is.

And so it’s not a “lake.” And it’s not an ocean from an ecological standpoint, but it’s oceanic in its vastness. So all the problems get multiplied, but it begins with the idea that people don’t understand the lake. And because they don’t understand it, they think it’s invincible. Again, Aldo Leopold said that “Our perceptions of nature, as in art, begin with the pretty and move through the beautiful and go to the meaningful.” And so people see Lake Superior as pretty. It takes a step for them to see it as beautiful because it’s hard to grasp and we can’t do anything in terms of preserving this lake until people have progressed from the pretty, through the beautiful, to having a real deep, meaningful connection with the lake. So whether it’s climate change or invasive species, the root of helping the lake begins with understanding its beauty and having a meaningful connection to it.

We only preserve the things that we love and we only love the things that we understand. And so the biggest part of our job at Friends of the Apostle Islands is not saying we need to solve this issue or that issue. The biggest job is to get people to love Lake Superior. When that meaningful connection is established, they step right up and say, “What can I do?”

__

Conserve School was an environmentally based semester residential program. That’s the brochure line. But the way to think of it is this: Everyone is familiar with students who want an immersive experience in another culture. Going to another country and immersing themselves in that culture for a semester. Well what we did was have high school students—mostly juniors—immerse themselves in active hands-on outdoor education. We would teach outside, climb trees, stand in water, read environmental literature.

My methodology as a teacher was to make sure my students occasionally got surprised. We would read John Muir’s wonderful essay, A Wind-storm in the Forests. He would climb up a tree to experience it more closely, to feel the tree moving. He talks about smelling the sap on your hands. He talks about literally feeling the tree swaying in the breeze. So, there was a beautiful white pine on campus that was very safe to climb and we would climb up into it and we would feel what he was talking about. And we would read what he was talking about. And I’d say, “Smell your hands.” You know, there’s white pine sap on your hands, and now it involves another sense.

Literature comes alive. I always said that literature should not be books on a dusty shelf. Literature is the story of what it means to be alive and human on Planet Earth. And part of that should be fun and beautiful and exciting. So I always tried to make it come alive. We would read Jack London’s story To build a Fire outside, building a fire. We would read Hemingway’s Big Two-Hearted River where Nick Adams goes fly fishing as his connection to nature after a traumatic time in World War One. And we would read it, fly fishing. We would do what the story was about as a way to connect with the characters in the story. To make that literature come off the shelf and be alive. And hopefully they remember some of those moments.

__

If I’m a student of the lake, which I consider myself always to be a student of the Apostle Islands and the lake, it’s constantly surprising. You never know what the waves are going to be, what the winds are going to be, where the Northern Lights are going to dance, what cave is going to be accessible, what the water temperatures will be.

__

When I think about peace, I think of it in several different ways. There’s kind of a personal peace. Are you at peace with who you are, your surroundings? Are you calm and open to learning from others? And then more of a communal sense. How do you relate to other people? Are you a person of peace in that you can relate to other people on a meaningful level without trying to necessarily change their ideas? Are you willing to listen? Are you willing to learn? Can you live in community with other human beings? How do you deal with conflict? Being a peaceful person doesn’t mean you don’t deal with conflict. It means that you know how to do it in a way that leaves both parties better.

And then the third one—again, it goes back to that Leopold idea and it’s more of a universal peace. One of the great powers of Aldo Leopold’s land ethic was that he took a very simple concept that everybody understands, about living an ethical life in a human community. And as he says in the book, he just threw a wider net and included the natural world. How do you put yourself at peace with the natural world around us? And that’s difficult because we live in a society, in a world, where resources are required to exist. How do we take those resources in a way that is respectful and is sustainable in the long run? We have to do that in a peaceful way. So I look at it in three ways, the personal way, personal peace. Communal peace in your community and peace in the larger sense, universal peace. Peace with the natural world around us.

__

As a national park, we get visitors from all over the world. They come here often in a very frenzied state. They come to the edge of the beaches and you can almost see them unwind. That incredible power of nature to heal and to slow people down. And often they leave here going, “If I could just spend more time here, if I could just have more of this in my life.” And in many ways, that’s what our national parks have become and are becoming is not just a physical place to be, but a place for emotional healing and for seeking out personal peace.

Here in the Apostle Islands, 80% of our park is designated as wilderness. So by legislative mandate, very little can be done to develop those areas. And so that protection is in place. The National Park Service has another level of protection, where there are certain things they will do and certain things they won’t do. There are already safe guards in place.

But more importantly, if people come here and they enjoy nature, they become more peaceful within themselves, and they carry that back to their communities. And they say, “Okay, I can’t go to the Apostle Islands or Yellowstone or Yosemite every day, but can I find a way to carry some of that back home with me in my own relationship to others. Is there a park nearby that I can go visit? Is there a lake I can paddle on? Can I put a plant in my house to remind me of the Apostle Islands? And then hopefully they are a little more relaxed. They understand their place in the universe a little better, and they can build peace around them. We can’t look at our national parks as an antidote or a prescription for peace. They are just a reminder that we have to build it in our everyday lives everywhere.

Lake Superior is big, but it’s not the whole world. And the peace that the lake and national parks can bring, have got to ripple out beyond the edges. I often fear for national parks in that they have become sort of like islands. I’ve seen people who wouldn’t throw a gum wrapper on the ground in the national park, pay no attention to a landfill going in, in their own community. I’m not equating those two directly, but I’m saying there’s an awareness of the specialness of a park. There also has to be an awareness of the specialness of your own backyard. And when we can do that, then the parks will not be such islands.

__

We talked about photography a lot, and photography is a really great way for people to slow down and pay attention. But really I’m a writer who takes pictures more than a photographer. And I believe in the sanctity of language. People see that when we talk about things like wedding vows, prayer, or even contracts to some extent. But I think all language needs to be seen as sacred. If we start treating it that way, the way we talk to each other, the way we frame our place in the world, what we put out there in terms of writing and put out there in terms of language will be much more thoughtful. Language is a pathway to peace, as much as national parks and photography. And it’s also something you can carry back home with you. As a writer, I’ve worked with a lot of young writers and they always ask me, “How often do you practice writing? How do you get better?”

Many of us spend the vast majority of our waking hours in our life using language. So if you begin to think of that as practice and you think of the sanctity of language and the sacredness of it, and you become thoughtful in your use of language, it’s like practicing 24/7.

__

I think that the beauty of the Apostle Islands is not just its physical beauty. In the 1930s, the National Park Service was looking for a place it could designate a park east of the Mississippi. Prior to that, the vast majority of our parks were in the wide open west. So they were looking for a place that could bring the national park experience closer to our population centers, which are mostly in the east. So they sent a guy named Harlan Kelsey up here in 1930 to tour three places.

Isle Royal, Michigan’s Porcupine Mountains and the Apostle Islands. And the Apostle Islands boosters, they really wanted this to be a national park. So they put on a show for this guy. They took him out in a yacht. They flew him around in an airplane. They wined and dined him and Harlan Kelsey said in a very famous speech for this area, that this area would never rise to national park quality. That it had been too much burned over, too logged, too quarried, too farmed, too destroyed. He might’ve been a little harsh, but he was probably right in the 1930s. But a funny thing happened in the 1930s, the Depression. And so a lot of the businesses that were happening on the islands ceased. There wasn’t much logging. There wasn’t much quarrying, all that stuff stopped. And the islands started to rebound ecologically.

And so by 1970, when Gaylord Nelson was pushing for this area to be a national park, they were pretty much healed. And people looked at them and thought nothing’s ever happened there, but it had. And the real message isn’t “Oh, they’re so pretty.” The real message to me is, “They’ve come back.” This should be a landscape of hope. And then in 2004, it got the ultimate accolade. And that was a dedication into the National Wilderness Preservation System, the highest level of protection. So it’s went from a pretty beat up landscape to a place that we gave some of our highest land management honors to, and why? Not because of something we did. Because of something we didn’t do. We just left it alone. Never underestimate the power of doing nothing. Allow nature or even human nature, time to heal and time to grow and time to recover. And you’d be quite surprised about the power of healing. I think there’s that lesson here.

__

Wallace Stegner said very famously in the 1960s that the National Parks are the best idea America ever had. Completely democratic, and showing us at our best. I think that was an aspirational statement back then for parks. It has to reflect everybody, the entire history from the indigenous peoples to the demographics of America today. The parks do belong to all of us, but the demographic of park users, the face of our national parks, it just doesn’t reflect that.

And so we need to build parks that are physically accessible. One out of five Americans has mobility issues. It’s 20% of the population. We have to have places for them to access, but accessibility is not just the physical. We have to have people of color feel comfortable coming to the parks. People who maybe English isn’t their first language might feel intimidated by a long list of park service regulations. That might be difficult for them to completely understand because English isn’t their first language. So we need to be able to provide them the comfort of speaking their language. It can be quite intimidating when the park is set up only for a specific type of person. And we need to open those gates for everybody. I’d love to see the Apostle Islands become a leader in that. And it could be through accessibility and through opening the park to make everybody feel comfortable here so that the Wallace Stegner quote is not aspirational, but reality.

__

Pay attention. Things get really interesting below the surface. Everywhere you are, wherever you are. There’s more going on than a superficial glance will reveal to you. And if you pay attention, which means sometimes silencing yourself and listening, engaging all of your senses. Pay attention to the people around you, pay attention to the history around you, pay attention to the relationship you have with the landscape around you. And things will get much more interesting and much more beautiful. That leads to a kind of humbleness because you begin to realize what a small piece of things you really understand. And hopefully that leads to a kind of peace within you that you don’t have to grasp it all. You just have to be attentive to the incredible wonder that life offers us.”

Discussion Questions:

-Richard K. Nelson said, “There is more to learn from climbing a single mountain a hundred times than climbing a hundred different mountains.” Do you agree?

-Are you more like John Muir or John Burroughs in your approach to nature?

-Have you experienced heightened awareness and observation during travel?

-How do you work to stay tuned into the beauty in your own back yard?

-Talk about a time you had to have patience in order to find the beauty you were looking for.

-Jeff talks about preserving the things we love and loving the things we understand. Share something you have learned to understand and love, and now want to preserve.

-Was there a teacher who inspired you with an unexpected approach to their subject?

-Is there a time when a natural environment brought peace to your life?

-Are there ways you can imagine language being sacred and helping to lead us toward peace?

-What are there ways you would like to practice paying more attention to the world around you?

This article was so meaningful to me. I am at my cabin in New Hampshire, on a little lake. I have come here for 45 years every summer, and since 2013 into the fall. Everything said in the article resonated with me. The way Mr. Rennicke connected love of nature and place with personal place, community peace and universal peace was so beautiful. Thank you.